A Guide to Aboriginal Art Styles

In as much of the way Indigenous art is regional in the knowledge and stories portrayed, it is equally regional in art style. Countless techniques exist across Australia as a means of conveying dreamings and spiritual connection. Since different communities employ various approaches, becoming familiar with Aboriginal art styles may help you recognise which area an artwork comes from!

In honour of NAIDOC Week (4 – 11 July, 2021), we take a look at just a few of the unique art styles through which Indigenous communities tell the oldest tales in the world.

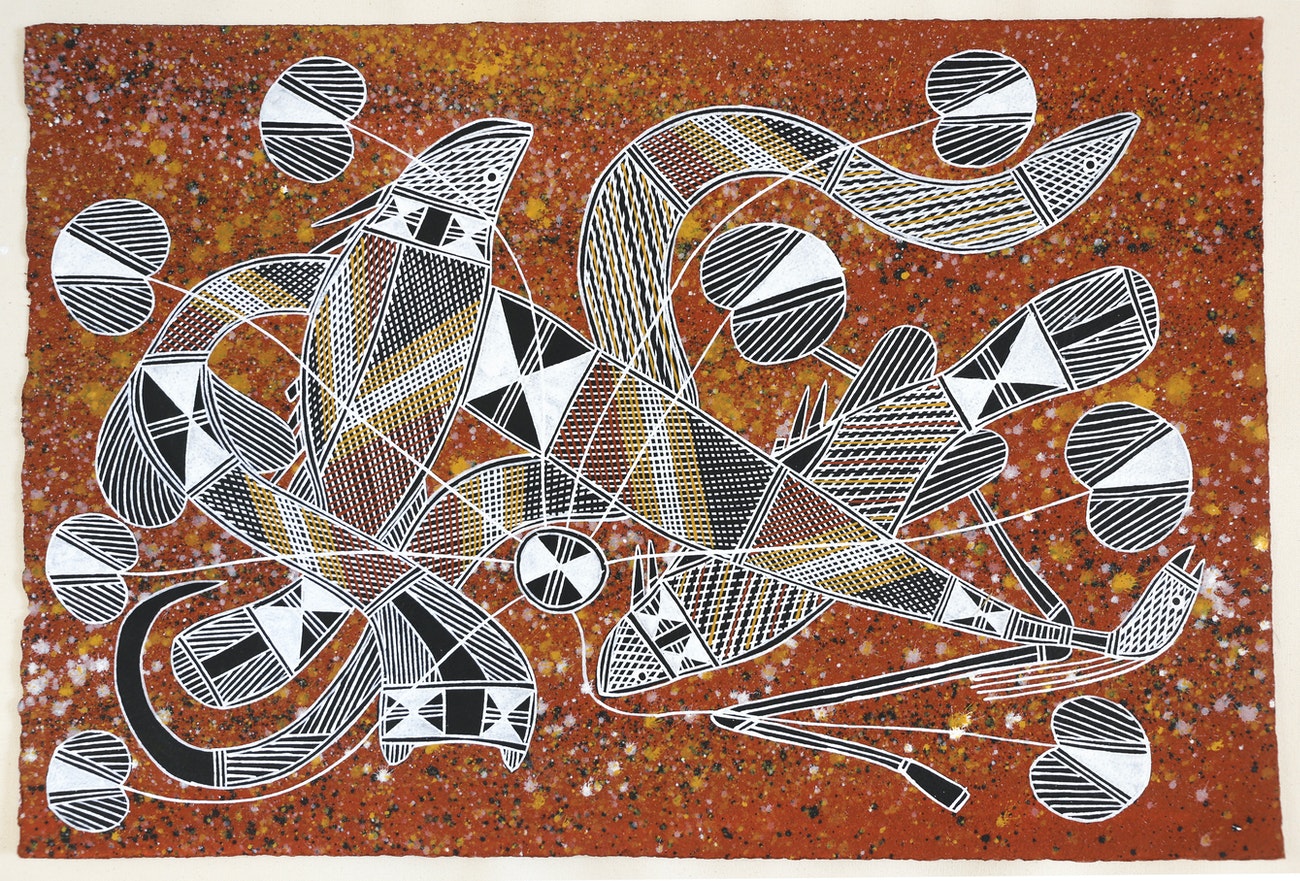

Rarrk (Cross-Hatching): Aboriginal Art Styles from NT

Cross hatching has long been used as an art style throughout civilisations old and new. The process of cross-hatching involves close parallel lines that fill or shade parts of a piece through a chosen medium. As an Indigenous art technique, rarrk is approached with more structure and stylisation than the general cross-hatching method calls for. It is largely used by Kunwinjku artists in the Northern Territory today. Injalak Arts, an Indigenous art centre based in Oenpelli, NT, particularly celebrates the unique style of rarrk and X-ray style figurative painting from West Arnhem Land.

“Rarrk is a painting technique used throughout Arnhem Land that originated with ceremonial painting,” Injalak’s studio coordinator Kerri Meehan explains. “The patterns are not just an aesthetic method of representation but also encode knowledge. There are ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ ways of describing and understanding paintings, and West Arnhem Land paintings can speak to Kunwinjku people who have passed through ceremony in ways that uninitiated people will not be privy to. Rarrk makes the paintings shimmer. In rock paintings this is usually simple parallel lines in red ochre. Many contemporary art works feature complex cross hatching in red, yellow, black and white. Internal organs of animals are often painted, a feature called ‘X-ray style’, a continuation of a painting tradition also found in rock art. The intricate patterns show the artists knowledge of the anatomy and the spiritual identity of animals as well as the powerful life forces that enmesh us together.

Komorlo (Egret) and Mandem (Waterlilly) was painted by Ezariah Kelly, who is noted for his use of bold lines, a strong sense of design and high visual impact.

“Barks are harvested from manbordokorr (Eucalyptus tetradonta or stringybark) for painting on. This is mostly during the Kunwinjku seasons of kudjewk (the wet season, from around December to March) through to yekke (the cold season, June/July). They must also be heated and cured over a fire before being flattened out in preparation for painting. Barks were used for shelter and people would often paint onto the bark surface to illustrate stories they were telling to family. Indeed, artists continue to paint on bark.”

“Fine rarrk is painted with manyilk, a brush made from sedge (Cyperas javanicus). The sedge stalk is shaved down until only a few fibres remain. The rarrk painted by Yirridja moiety artists is fine whereas Duwa moiety artists can be recognised for thicker lines.”

“A contemporary painting medium used by Kunwinjku artists is Arches 640gsm handmade watercolour paper. Arches paper is robust with an organic textured surface and has proved to be a natural complement to working on bark and is available year round.”

We recently spoke to Injalak Arts on what it means to be an Indigenous art centre. Read the full story here.

Watercolour: Modern Techniques and Traditional Stories

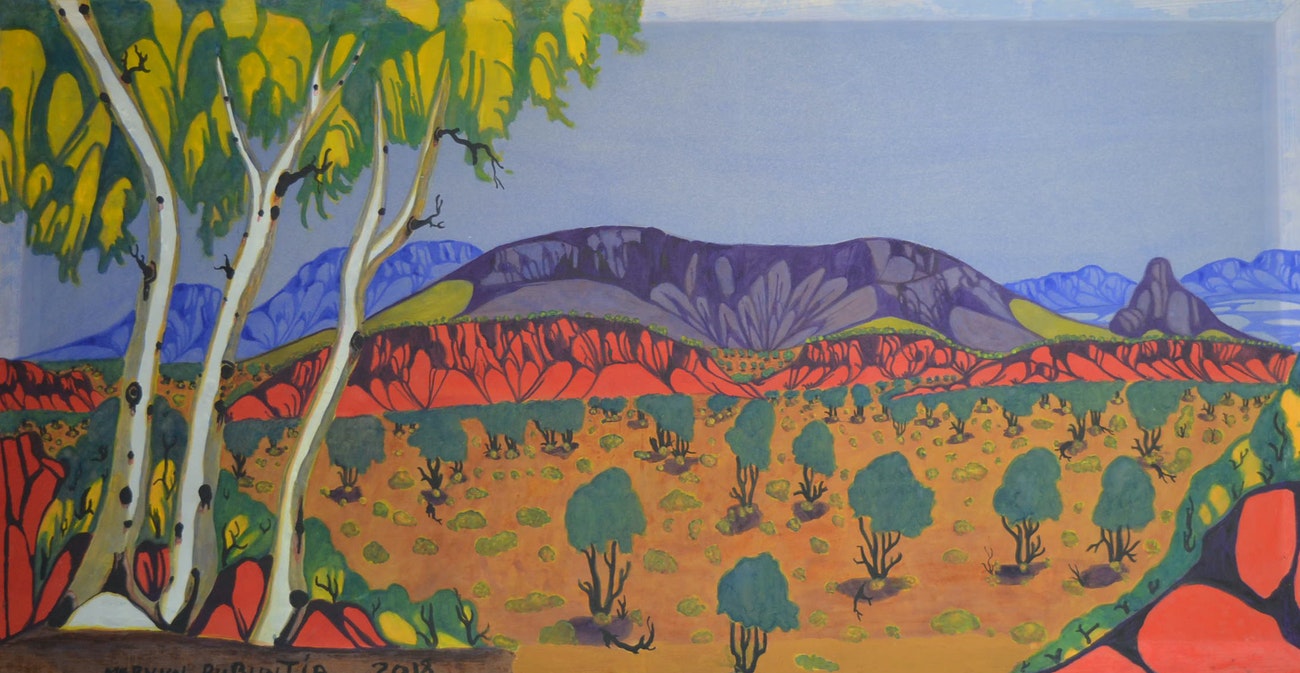

Among some of the most recognisable Indigenous artists groups and Aboriginal art styles are the watercolour painters of Central Australia. This refreshed approach to traditional storytelling primarily began with Albert Namatjira, arguably one of Australia’s most famous artists of the 20th century. Namatjira taught his children this unique watercolour-based technique, who have since passed the teachings onto their children. Ultimately, a legacy of watercolour artists in the Central Desert region has grown into the popular style we see today. In continuing his legacy, these artists sustain an important piece of living history.

Mervyn Rubuntja and his illuminated bus, part of last year’s Parrtjima – a Festival of Light.

Iltja Ntjarra / Many Hands Art Centre is the home of the Namatjira watercolour artists. For over 15 years, it has offered Arrernte Artists a space to come together to paint, share and learn more of these new techniques and ideas. The principles of Many Hands are based on the importance of watercolour painting as one of the Aboriginal art styles, and extend to welcome youth and landscape artists to paint with their community. In doing this, the art centre passes down stories related to their country and culture, as well as supporting their culture and improving the artists’ economic situation.

Mervyn paints the land he grew up on, Rwetyepme/Mt Sonder, Central Australia.

“The artists paint their country and where they are from,” Iris from Many Hands tells us. “They like to show people their country and share their culture with everyone. We have artists that paint different styles and colour pallets. They always share their techniques and support each other to better themselves with their artwork. They all have a story that goes with their paintings and why they paint it. Culture is a big part of our art centre and artists, especially when we travel out bush to paint on country.”

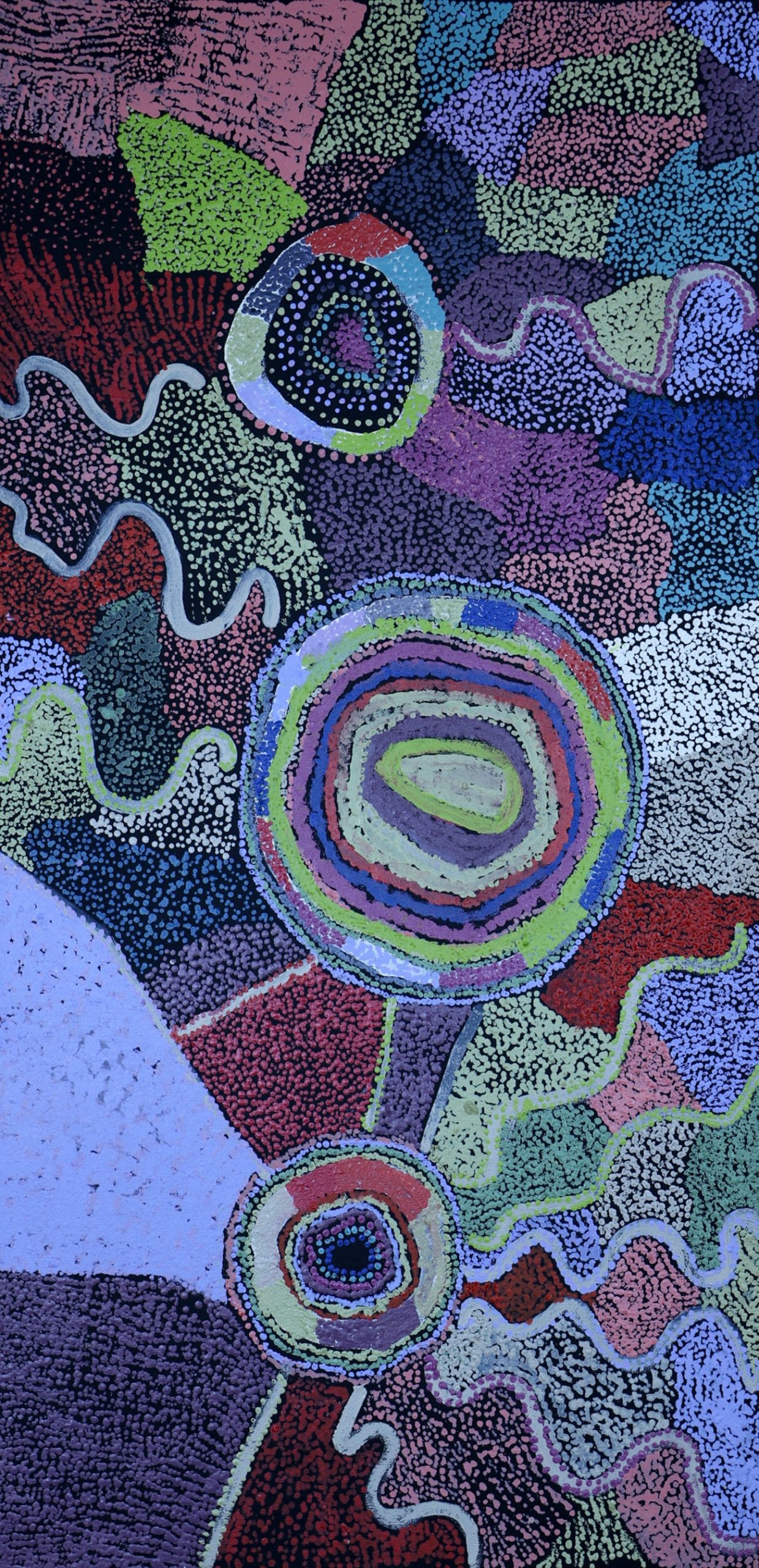

Dot Painting: A Renowned Indigenous Art Style

Not only is the iconic dot style of Aboriginal art an intricate aesthetic to the eye; it continues to disguise the deeper sacred meanings within the stories the paintings tell. Dot paintings are one of the most prolific Indigenous art styles, and often are misunderstood as a form of Aboriginal art that is practised by all communities.

Through her use of colour, circles and faint dots, Bush Tucker by Veronica Daniels of Warlayirti utilises popular characteristics of Aboriginal art.

Before the canvas, Aboriginal communities would draw into sand the sacred designs which aligned with specific ceremonies. Body-painting also carried this symbolic nature of storytelling. Fast forward to the 1970s; Aboriginal communities were encouraged to share their stories on murals and more permanent materials. To protect the sacred character of the symbols, the designs were disguised through a new art style: the dot painting.

Weaving: An Ancient Art Style

As an ancient tradition that has been a pillar of cultural maintenance, weaving is an art technique practised by women of predominantly remote communities. Using natural fibres and dyes from the bush, there is a long-standing history of women making objects for ceremonial and daily use. Through present-day organisations, the skills that have traditionally crafted baskets and other practical items, evolved into more experimental sculptural forms that embody important characters of Indigenous culture.

A closer look at the skilled weaving of a Papa by Rochelle Ferguson. Click here to see the whole sculpture!

One widely celebrated organisation working with these communities today is Tjanpi Desert Weavers of the Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (NPY) Women’s Council. As a representative of more than 400 Aboriginal women artists from 26 remote communities on the NPY lands, Tjanpi was created to enable women in the remote central desert regions to earn their own income from fibre art. For their local artists, the cultural connection to the art technique is ever-present through the process. Women come together to collect grass for their art, as well as to hunt and gather food, teach children about Country, and perform cultural songs and dance (inma). Together, this forms the “bloodline of the desert weaving phenomenon”.

This vibrant little Papa by Rachael Yaritji Stevens is made of all natural bush dyes and materials.

NAIDOC Week is now expected to take place in November this year. With many of the fairs and events that normally bolster Indigenous art centres throughout the year cancelled, we can continue to support remote communities through purchasing and sharing artworks from these art centres. Discover more Aboriginal art here.