Mahalia Mabo and the Mabo Legacy

Mabo – as Australians, we all recognise the name and admire the legacy, but have you ever thought about the Mabo family who have continued this legacy over the decades? Mahalia Mabo is a proud Manbarra, Nywaigi and Meriam woman who comes from a long line of artists and activists. Mahalia’s paternal grandfather, the late Eddie Mabo, was a Torres Strait Islander community leader who fought for the recognition of Indigenous land rights. Mahalia began focussing her time on creating art at the beginning of this year and has already blown us away with her bold, vibrant artwork that tells the stories of her childhood and life. We chat to Mahalia about her artistic journey and family.

Mahalia Mabo signing an artwork.

Mahalia’s Art Journey

Mahalia grew up surrounded by artists, and most of her earliest memories were based on art. Many of Mahalia’s family members were – and are – artists. A long line of creativity that spans several generations, her paternal grandparents, parents, sisters, and now her own children all have the creative flair.

Mahalia Mabo with her father and two children with Piadram face markings for Mabo Day.

As a child, a rule in the Mabo household was no watching TV – especially the Simpsons! But Mahalia and her sisters had endless opportunities to create art and use their imaginations. This early introduction to art allowed Mahalia to explore numerous different artforms, from watercolour to paper-mache, clay making and sculpting. But it wasn’t until Mahalia was an adult that she learnt how to use acrylic paint during a paint-and-sip night with friends. Acrylic quickly became the artform she predominantly uses to create her vibrant pieces.

Due to intergenerational trauma, mental health issues as a result of childhood trauma, and a late diagnosis of ADHD at 35, Mahalia has at times struggled to navigate through life. Recently, however, Mahalia picked up a paintbrush and discovered that art could serve as a healthy coping mechanism for her trauma. Mahalia describes her new-found passion for art as “the most amazing release,” which has had “the most amazing impact on me, my mental health, my life overall.” When asked why she paints with such bright vibrant colours, she explains, “because it reflects that feeling of joy [and] pure happiness that I feel when I do paint and when I can be creative.”

Mahalia feels an intense desire to keep the vibrancy, beauty and fun of her art consistent through her practice: “I want that to be laid out on the canvas for people to see.”

While art was always a big part of her life, it was only this year that Mahalia began to focus much of her time on this creative pursuit. Living in Meanjin (Brisbane), Mahalia relocated to an “artsy” neighbourhood, walking distance to the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art and Maiwar, the Brisbane River. These creative surroundings inspired Mahalia to revisit and explore her creative roots at the beginning of 2022.

Mahalia’s Art Process

A fantastic creative release, Mahalia tries to paint every morning before work, often having many pieces on the go at once. As a symptom of her ADHD, Mahalia explains, “I’ll start something and then it’ll sit there for a while until I can eventually finish it.” This means that she’ll jump between pieces, continuing whichever piece she feels connected to on that particular day. For Mahalia, creating art is a means of maintaining her mental health and managing ADHD, rather than purely a business pursuit.

When asked what sorts of stories she tells through her paintings, Mahalia reveals, “I am an intuitive artist. Most of my art comes from my memories as a child with my family, especially my grandmother… She was the most phenomenal woman I’ve ever met… She was an activist, she was an artist, she was a creative, she was a mother of ten, she was a sibling of ten, she was a sugar slave descendent, she just had so much to give and to learn from.” A lot of Mahalia’s work is therefore based around memories with her Aboriginal grandmother from their home on Hibiscus Street. The culture, love and affection felt in that house was unparalleled for Mahalia, and the keen artist wants to reflect this love on her canvases.

Some of Mahalia’s artworks are accompanied by stories she has written of memories from her childhood. Her artwork Seeds of Yesterday 2 is accompanied by the following story:

We’d sit in the water apple tree out the front, talking and laughing. We didn’t call them water apples though. They were Ero’s we’d eat ‘em till our bellies were full or all the ripe ones were gone, whichever came first. My Ata (grandfather) planted that tree from seeds from Mer and its seeds had dispersed around the neighbourhood. Once, we sold a white plastic bag full of Ero’s to the old fulla across the road. Not sure how much we charged for them but he paid and took the whole bag, even though he had his own water apple tree in his front yard…

The Mabo Legacy

Mabo is a household name in this country, and for good reason. Eddie Mabo was instrumental in the Indigenous Land Rights Movement in Australia and headed the Mabo vs Queensland (1992) court case, which saw the recognition of the pre-colonial land interests of First Nations peoples. Eddie’s determination led to the Native Title Act of 1998, resulting in the official recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ land rights in Australia.

When asked what it was like to grow up as a descendant of Eddie Mabo, Mahalia states, “it’s who I am, I don’t know any different. I just feel so strongly about Aboriginal and Torres Islander People’s rights and systemic change.”

Eddie’s wife – Mahalia’s paternal grandmother – Dr. Bonita Mabo was a proud Manbarra and Nywaiga woman, and sugar slave descendant. Together, Eddie and Bonita inspired not only their own family, but an entire country for generations to come. Mahalia lost her grandfather, Eddie, at the age of 5, before the 1992 court case result was revealed. But Mahalia still has “really fond memories of him” from this time. Having such inspirational grandparents meant there were, as Mahalia states, “big shoes to fill.”

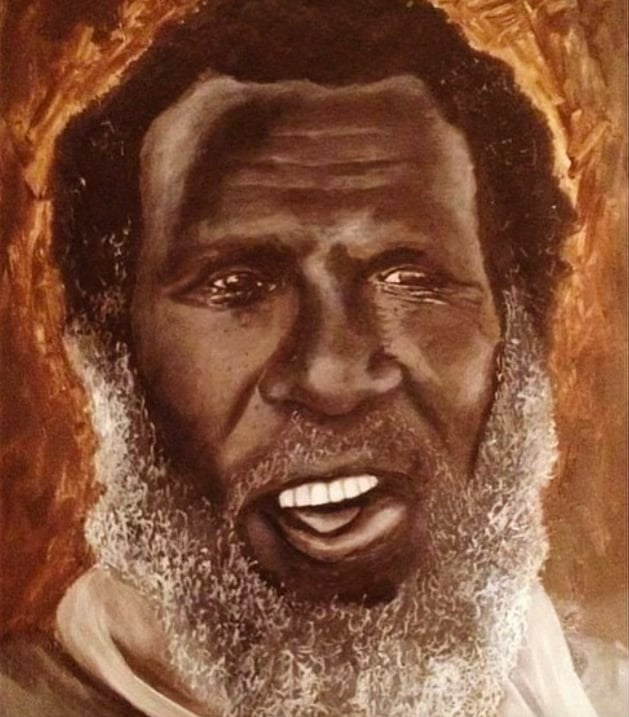

A painting of Eddie Mabo by Boneta-Marie Mabo, Mahalia’s sister.

Mahalia explains that growing up “right in and amongst” the activism of her inspirational grandparents “really taught us to be really unapologetically Black and to be really proud of who we are and where we come from, even though, growing up, everything around us was telling us not to be proud of our Blackness, not to be proud of our Aboriginality, not to be proud of our cultures.” Because of the pathway Eddie and other members of the Mabo family paved for Mahalia, despite the White society Mahalia was surrounded by and could continually feel every day, it was instilled in her to always be proud of who she is and her history, and to always stand proud in her Blackness.

How Can the Art Industry Better Support Indigenous Artists?

After only a few months of sharing her art online, Mahalia was approached by a non-Aboriginal owned company to use her artwork on merchandise. As an Analyst and having previously worked as an Investigator for the government, Mahalia knows the importance of carefully reviewing the terms of any contract and ensuring they are suitable for her. Mahalia therefore had the upper-hand when the company was trying to undercut her by only offering her 5% royalty fees. As such, Mahalia was quick to shut the offer down, as she would not be receiving the remuneration she deserved.

Unfortunately, stories like this are not isolated, nor are they uncommon. Artists – and particularly Indigenous artists – are often undercut by larger non-Indigenous owned businesses who exclusively commodify Indigenous designs and cultures for profit, while appearing to be Black-led. There are many non-Indigenous owned businesses that commodify Aboriginal Art and cultures, but who don’t comply with the Indigenous Art Code. Such capitalisation of Indigenous designs by non-Indigenous owned businesses is known as ‘Black cladding’. Mahalia rightly argues that Indigenous artists must be paid what they’re deserved, and the artists who are unable to stand up for themselves should be better supported by the wider community and the Arts industry as a whole, so that the exploitation of Black artists does not continue to occur.

Mahalia hopes her art “inspires people to look into whose country they’re standing on, and serves as a reminder that Aboriginal sovereignty was never ceded.”

Mahalia is a finalist in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander category of the Bluethumb Art Prize 2022. You can vote for her artwork, Coral Dreaming 2, in the People’s Choice Award for your chance to win your favourite artwork valued up to $2,000!

Want to see more artists who come from creative families? Browse our latest curation to see the Bluethumb artists bonded by blood and by love.